The Process of Filmmaking

Film is a young medium, at least compared to most other media. Painting, literature, dance and theater have existed for thousand of years, but film came into existance only a little more than a century ago. Yet in this fairly short span, the newcomer has established itself as an energetic and powerful art form.

"Motion pictures are so much a part of our lives that it's hard to imagine a world without them. We enjoy them in theaters, at home, in offices, in cars and buses, and on airplanes. We carry films with us in our laptops and iPods. We press the button, and our machines conjure up movies for our pleasure. For about 100 years, people have been trying to understand why this medium has so captivated us. Films communicate information and ideas, and they show us places and ways of life we might not otherwise know".[2]

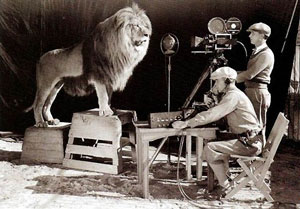

More than most arts, film depends on complex technology. Without machines, movies wouldn't move, and filmmakers would have no tools. In addition, film art usually requires collaboration among many participants, people who follow well-proven work routines. The key to a well- maintained set is to have a good crew filled with people who are organized and coordinated. In most cases, working on a film crew requires many more hours than the normal nine-to-five job. With various temperaments, egos, technical snafus, and acts of God, which can all play a part into the picture, a movie set is a hotbed of excitement, uncertainty, and creativity.

Dawns of Filmmaking

Early films dating from the 1890s were far shorter and less technically complex than feature films in the twenty-first century. As a rule, they did not require either a script or a large crew. Many were nonfictional films, known as actualités , which in some instances simply involved setting the camera up in front of a street scene (or other view), filming for a short while, developing and printing the film, and then screening it unedited. The Lumière brothers' celebrated Cinématographe served this type of filmmaking well, as it was a movie camera, printer, and projector all in one. A camera operator equipped with this device could be supplied to vaudeville theaters, which regularly included films in their program; he or she would film local scenes, print them, and project them, all on the same day.

Other popular genres of the time were filmed variety acts and "trick films," which centered on special effects. These films, unlike their documentary counterparts, required staging, rudimentary sets, costumes, and props. Trick films also demanded more innovative production techniques than actualités or variety acts. For example, The Execution of Mary, Queen of Scots (1895) involved stopping the camera after Robert Thomae, the actor playing Mary, laid his head on the execution block, and then using a dummy for the head-chopping sequence.

Trick films and variety acts were most easily made in a studio. The Execution of Mary, Queen of Scots was shot in the first dedicated film studio: Thomas Edison's "Black Maria," which opened in New Jersey in 1892. Although basic by modern standards, it was carefully designed to deal with the various contingencies that filmmaking faced at the time. It had an open roof to allow in sunlight—essential for a period when all filming relied on natural light—and the whole structure rested on a revolving pivot to maintain an alignment with the sun. Other filmmakers followed suit, both in the United States and abroad, including the Biograph Company, which built a rooftop studio in New York in 1896, and Georges Mélies (1861–1938), who constructed a glass-encased studio near Paris in 1897.

Staged films demanded preplanning. In the early days, however, this tended to be minimal and was left mostly in the hands of the film's director. As film companies moved towards mass production, more methodical planning processes were instituted. Careful scheduling allowed efficient use of resources and also ensured a regular flow of product. Increasingly, producers rather than directors assumed greater control over planning projects. Directors, for their part, were progressively relegated to the role of project managers, subject to strict schedule and budgetary controls, and required to shoot the film according to a script developed elsewhere in the system.

Two important management innovations did much to change the balance of power between producers and directors. The first was the institution of production schedules around 1907 to 1909. The second was the introduction of continuity scripts, which were in regular use by the early 1910s. Production schedules helped to manage the flow of activity in order to ensure maximum utilization of studio capacity and human resources. These production schedules depended, in turn, on continuity scripts which provided detailed outlines of each individual film project. As longer narrative films became the dominant type of film production, continuity scripts played the crucial role of indicating the resources such as actors, crew, set, and equipment that would be needed for the production as well as ensuring that the plots were well planned in advance. While these innovations came about partly in response to a growing reliance on narrative films, making it easier to plan and produce them reinforced the eventual dominance of this type of film.

This system, which was firmly entrenched by 1916, came to be known as the "multiple director-unit system." Under this system, each company had several filmmaking units, with each unit headed by a director and including a full production crew. Other resources, such as actors, were drawn from pooled resources which the production company made available to each unit as required. Later modifications to this scheme led to the "central producer system" in which producers took responsibility for supervising a number of simultaneous productions and over-seeing the directors who worked on them. This way of organizing film production was the basis of the system used throughout the US "studio era" (1920–1960), which was dominated by a handful of large, integrated production - distribution - exhibition companies. It quickly came to be seen as a model of best practice for other national

industries, many of which adopted its techniques. The production process established under the US studio system remains in use and dominates filmmaking to this day. There are various reasons for the survival and dominance of this model. To begin with, many of the basic technical requirements of filmmaking have not changed significantly over the years. Second, most of the skills needed for making films are now embedded in craft knowledge and professional practices protected by unions and occupational communities. Finally, the systems of project management that were refined during the studio era continue to yield significant practical and economic benefits. Although the different stages of the production process were developed to meet the needs of live-action fictional feature films, many aspects of this system are used to produce other types of films, such as documentaries and shorts.

The Process of Filmmaking

Filmmaking (often referred to in an academic context as film production) is the process of making a film, from an initial story, idea, or commission, through scriptwriting, casting, shooting, directing, editing, and screening the finished product before an audience that may result in a theatrical release or television program. Filmmaking takes place all over the planet in a huge range of economic, social, and political contexts, and using a variety of technologies and cinematic techniques. Typically, it involves a large number of people, and takes from a few months to several years to complete, although it may take longer if there are production issues, and the record for the longest production time for a major film is The Princess and the Cobbler (1993) - 28 years development.

Filmmaking practices used to create different types of film can vary greatly. The production processes of a live-action film and an animated film, for instance, will differ substantially. Nevertheless, the main stages through which production moves, are normally clearly identifiable regardless of the type of film involved. This process is conventionally divided into four parts:

- Development, which deals with conceiving, planning, and financing the film project;

- Preproduction, when key resources such as cast, crew, and sets are assembled and prepared;

- Production, during which time the film is actually shot;

- Postproduction, which involves editing the raw footage and sound, executing special effects, inserting music or extra dialogue, and adding titles.

In this phase, the producer conceives an idea for a movie, develops it into a presentable package and tries to raise production funds to get the project into preproduction. "The development process sounds simple, but let’s take a closer look. First, the producer searches for material that can be turned into a successful (that is, financially successful) motion picture. Inspiration might come from an original screenplay, novel, stage play, short story, book, periodical, real-life story, pop song, or another motion picture. Regardless of its source, the producer must acquire or option the rights to it before making the movie. If an intellectual property is being optioned it means that there is usually a certain time limit (mostly one year with the possibility of a prolongation for another 12 months) during which time the producer must be ready to pay the full amount of the previously agreed-upon full price. This does not necessarily mean the producer must get shooting, but it means he has to purchase the property completely.

If the screenplay will be based on an existing novel, play, short story, or book, the producer first must obtain the rights to have the screenplay written (assuming the property is not in the public domain). The time needed to negotiate adaptation rights and then to obtain a finished, presentable screenplay, including rewrites and the like, can be considerable - several months to a year or two.

Next, to raise money for production, the producer must find a production company or studio willing to provide financing. This is where the process of packaging begins. The producer must create an attractive overall package. “Name” actors who will guarantee the film’s success must be found. The producer might also seek a well-known director to guarantee the financiers that a professional and superior product will be created. However, “name” actors and directors will only agree to be in a movie if distribution is guaranteed, and to get a distribution contract, commitments are required from the actors and director. It is a vicious circle.

When dealing with “name” talent (in reality, this means dealing with their agents, managers, personal advisers, astrologers, friends, and trustees), the producer must accept their “right” to creative participation. In the end, it is the talent’s face and name that are remembered with the screenplay. As a result, the screenplay must often go through new rounds of rewrites to accommodate the wishes of the talent. All this takes time - and money. The process is successfully concluded when the producer has all the names he or she wants - or is satisfied with - and has obtained their written consent to be part of the production.

After the producer has found inspiration for a film, has cleared the rights to the screenplay or other material on which the film will be based, and has obtained commitments from actors and a director, he prepares a film pitch, or treatment, and present it to studios, networks, potential financiers and distributors. If the pitch is successful, the film receives a "green light", meaning someone offers financial backing: typically a major film studio, film council, or independent investor. Now he has all the talent desired, a final screenplay, and financial backing. A substantial amount of money has been advanced and is on account and ready to be drawn. The producer might even have distribution. In other words, it’s a go! The production is now ready to move into preproduction".[1]

During the studio era, development and planning was undertaken by company executives and was shaped by two factors: first, by the estimates made by the head of distribution as to the number and nature of films required to meet theatrical exhibition needs; and second, by the need to make optimal use of internally held resources such as specialized staff, sets, and costumes. Top studio executives decided the overall budget for the year, and based on this budget, allocated expenditures for individual motion-picture projects.

Once the range of projects was decided in terms of budget and genre, work commenced on planning the individual films. Projects normally originated with the script department, a unit all major producers had instituted by 1911. Normally, potential scripts were selected by readers from existing sources such as novels, plays, radio shows, or even existing movies. The Wizard of Oz (1939), for instance, had previously existed in all these forms by the time it was put into production. Other films began life as original screenplays, normally by writers under contract to the studio, since producers rarely purchased original screenplays from freelance writers for fear of copyright infringement.

Whilst some projects were selected on their individual merits, many were genre pieces or sequels that capitalized on proven success and available resources. Examples include the Warner Bros.' musical

Gold Diggers of 1933 (1933) and Universal's horror franchise entry,

Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man (1943). Some scripts were commissioned as vehicles for contracted stars, such as

Road to Morocco (1942), which was one of a series of original scripts written for Bob Hope and Bing Crosby.

Once the script department had made its recommendations for potential productions, selected scripts were allocated to associate producers who oversaw the development and production process. This process normally began with a scenario describing the plot in prose form. It was followed by a treatment providing more detail about individual scenes. Next a screenplay was prepared which included dialogue. Finally, a shooting script broke the action down into individual shots and provided guidance for staging and camera positioning.

Scripts conformed to a standardized format, with brief camera and set instructions in the left-hand column and dialogue to the right. Each step of the process was subjected to detailed critical evaluation and numerous revisions before it was allowed to progress to the next stage of writing. As the project evolved, other elements of the production, such as casting, were discussed and decided, and these decisions in turn often led to further script development. The successive drafts were often the product of different writers. Some received on-screen credit and others did not. Carried to an extreme, this process resulted in films such as Forever and a Day (1943), which credited the contributions of an astonishing twenty-one writers.

The meticulous process of script development was intended to ensure not only that the story would be entertaining and engaging, and hence popular with audiences, but also that the resources needed to transform it into a film were available, and that the entire process could be performed within budget and on schedule. The continuity script acted as a blueprint for the tasks required during preproduction, such as casting and set building. Once filming began, it functioned as a detailed template for the day-to-day activities involved in shooting the film. The tasks to be performed, such as the creation of different camera setups, were known in advance and therefore could be scheduled for maximum efficiency. The continuity script also had the added virtue of making it far easier for the production office to monitor the progress of the shooting, and to intervene early when problems arose. This often occurred when scenes proved unexpectedly difficult and expensive to shoot, and could lead to ongoing script revision.

During the studio era, planning and resource allocation decisions were made within the context of multiple projects. The logic was one of portfolio investment in which decisions on individual projects were strongly related to what the studio intended to produce and release in a given year. The breakdown of the studio system in the early 1950s saw a return to the planning of films as individual units, a process known as the "package-unit system." This approach became dominant through the 1950s and 1960s when the studios began to cut back production. The cutback was partly a response to antitrust decrees that forced the studios to dispose of their exhibition business, with consequent loss of control over release. It also responded to the decline in cinema attendance, which was caused by a range of factors such as the baby boom and the growing popularity of television. The production cutbacks meant it was no longer viable for the studios to retain costly personnel under contract. Nor was it worthwhile, once control over exhibition was lost, to maintain an infrastructure that depended on a continuous flow of film production.

In pre-production, every step of actually creating the film is carefully designed and planned. The production company is created and a production office established. The production is storyboarded and visualized with the help of illustrators and concept artists. A production budget is drawn up to plan expenditures for the film. For major productions, insurance is procured to protect against accidents.

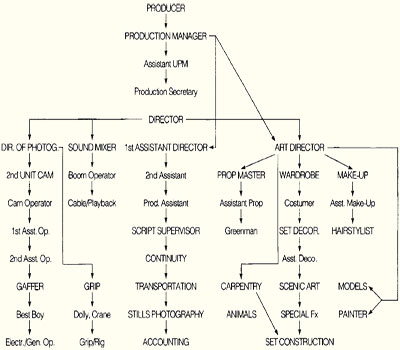

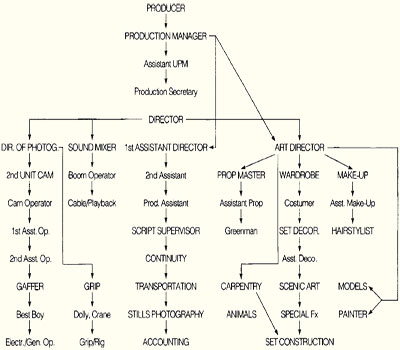

The producer hires a crew. The nature of the film, and the budget, determine the size and type of crew used during filmmaking. These are typical crew positions:

- The director is primarily responsible for the storytelling, creative decisions and acting of the film.

- The assistant director (AD) manages the shooting schedule and logistics of the production, among other tasks. There are several types of AD, each with different responsibilities.

- The casting director finds actors to fill the parts in the script. This normally requires that actors audition.

- The location manager finds and manages film locations. Most pictures are shot in the controllable environment of a studio sound stage but occasionally, outdoor sequences call for filming on location.

- The production manager manages the production budget and production schedule. They also report, on behalf of the production office, to the studio executives or financiers of the film.

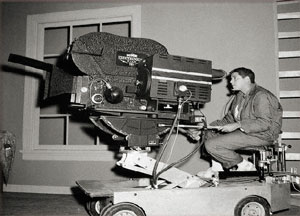

- The director of photography (DoP) is the cinematographer who supervises the photography of the entire film

- The director of audiography (DoA) is the audiographer who supervises the audiography of the entire film. For productions in the Western world this role is also known as either sound designer or supervising sound editor.

- The production designer creates the visual conception of the film, working with the art director.

|

|

| Organizational chart for preproduction and principal photography |

|

- The production sound mixer is the head of the sound department during the production stage of filmmaking. They record and mix the audio on set - dialogue, presence and sound effects in mono and ambience in stereo. They work with the boom operator, Director, DoA, DoP, and First AD.

- The sound designer creates the aural conception of the film, working with the supervising sound editor. On some productions the sound designer plays the role of a director of audiography.

- The composer creates new music for the film. (usually not until post-production)

- The art director manages the art department, which makes production sets

- The costume designer creates the clothing for the characters in the film working closely with the actors, as well as other departments.

- The make up and hair designer works closely with the costume designer in addition to create a certain look for a character.

- The storyboard artist creates visual images to help the director and production designer communicate their ideas to the production team.

- The choreographer creates and coordinates the movement and dance - typically for musicals. Some films also credit a fight choreographer.

|

Early preparations begin for the actual filming. Director, cast, and film crew are assigned while script development continues. Suggestions made by the director are incorporated, and the script is tailored to fit the image of the selected stars. Each member of the crew is provided with a copy of the script to assist preparations for principal photography. Decisions are made about which parts of the film will be shot on studio sets, and which on location. In general, studio shooting is preferred as it allows a greater degree of control over both the artistic and practical elements of the production process, and avoids the expense of transporting and accommodating cast, crew, and equipment. Filming on location is preferred for greater realism. If it is a location shoot, locations are selected during preproduction and all the practical arrangements are made in preparation for the arrival of the cast and crew.

Under the studio system, the larger production companies employed not only a variety of sound stages, but also extensive grounds on which potentially flexible sets remained standing for repeated use. For instance, parts of the Jerusalem set built for Cecil B. DeMille's The King of Kings (1927) can also be seen in King Kong (1933), The Garden of Allah (1936), and Gone with the Wind (1939), amongst other films. The redressing of sets, with superficial alterations, disguised their repeated use and was an important factor in the economy of the studio system. Standing sets would be readied for production and new sets built when necessary (although the latter expensive and time-consuming activity was avoided when possible). In addition to standing sets, the large studios also maintained vast collections of costumes, furniture, fake weapons, and even live animals, all of which individual productions could book for use. During the studio era these activities were organized internally by heads of departments who worked to ensure that all these resources were selected and made ready during preproduction. Following the dismantling of the studio system, it has become common for productions to rent studio space, costumes, props, and other materials from independent businesses that provide specialized services to the film industry. Before filming begins, a shooting schedule is prepared. This describes the order in which scenes will be filmed, which usually differs from the order in which they will appear in the finished film. The plan allows the film to be shot as quickly and cheaply as possible. All the scenes using a particular set or location are normally shot consecutively. The availability of actors can also dictate the order in which scenes are filmed. For instance, Goldfinger (1964) began shooting in Miami without its star Sean Connery, who was still working on Marnie (1964) at the time. Goldfinger 's Fontainebleau Hotel set later had to be reconstructed at Pinewood Studios in England once Connery became available, and back projection was used to incorporate footage shot on location.

Some directors regard the practice of shooting out of sequence as artistically compromising. In some rare instances directors insist on shooting films completely in sequence—a practice that allows actors to fully engage with their roles, but is costly in other respects. Ken Loach, the British director of Raining Stones (1993), Ladybird, Ladybird (1994), and Sweet Sixteen (2002), is one famous advocate of shooting in sequence, since strong performances are always the lynchpin of his films.

In production, the video production/film is created and shot. More crew will be recruited at this stage, such as the property master, script supervisor, assistant directors, stills photographer, picture editor, and sound editors. These are just the most common roles in filmmaking; the production office will be free to create any unique blend of roles to suit the various responsibilities possible during the production of a film.

By the first day of filming, every member of the crew is expected to be familiar with the shooting schedule, and all the necessary equipment for the day's work should be available. Each member of the crew is provided with a call sheet, itemizing when and why they are required on set. Actors usually have their own separate call times. The sets will have been built and dressed, and lights positioned in accordance with the scheme agreed by the director and the director of photography. Cameras and microphones are positioned and camera movements and lighting adjustments are rehearsed with the help of standins who walk through the actions. Marks are placed on the floor to ensure that actors make the same movements when the scene is shot. While this is going on, the actors spend time in costume, hair, and makeup. Once the technical aspects of shooting the scene have been firmly established and the actors are dressed, they are called to the set. At the discretion of the director, some time is normally spent rehearsing before the scene is filmed.

When the director is ready to shoot, an assistant calls for silence. If filming takes place in a studio, the doors are closed and a red light switched on above them to signal that entry to the set is forbidden. The director instructs the camera operator and sound recordist to begin recording. The scene and take numbers are read out and the hinged clapperboard snapped shut, which assists with marrying sound and image in postproduction. The director then calls "action" and the actors begin their performance.

The first take is not always successful. It may be spoiled by actors flubbing their lines or marred by errors in camera movement or focus, or by lights or microphones making their way into the frame. Repeated takes are therefore often unavoidable. Some directors, such as W. S. Van Dyke, nicknamed "One-Take Woody," have always endeavored to keep these to a minimum, while others, such as Fritz Lang and Stanley Kubrick, developed reputations for demanding an extraordinarily high number of takes before their exacting standards were met. Few go to such extremes as Charlie Chaplin did when he went through 342 takes of a scene in City Lights (1931) in which his Little Tramp buys a flower from the blind girl (Virginia Cherrill). In general, careful planning and rehearsal can help keep the number down and reduce unnecessary waste of expensive film stock.

The difficulty of deciding whether a take is satisfactory has been much reduced since video was introduced into the process. The practice was pioneered by the actor and director Jerry Lewis when filming his feature debut, The Bellboy (1960), in which he also starred. Lewis sought a way to instantly review the recording of his acting performance. He decided to use a video camera linked to the main film camera and recording the same material. This invention came to be known as the "video assist." The recent advent of digital filmmaking has meant not only that master footage can be viewed at any time, but also that it is economically realistic for the director to request a greater number of takes than with 35mm, or even 16mm, film stock, since digital videotapes are considerably less expensive.

When the director is satisfied with a take, he or she will ask for it to be printed. The same scene may still need to filmed again from different camera angles, though. Alternatively, a scene may be shot with more than one camera at once. This allows a range of options when it comes to editing, and it is an especially valuable technique where a scene can only be filmed once due to danger or expense. Gone with the Wind , for instance, used all seven of the Technicolor cameras then in existence to shoot the sequence depicting the burning of Atlanta.

At the end of the day, the director approves the next day's shooting schedule and a daily progress report is sent to the production office. This includes the report sheets from continuity, sound, and camera teams. Call sheets are distributed to the cast and crew to tell them when and where to turn up the next shooting day. Later on, the director, producer, other department heads, and, sometimes, the cast, may gather to watch that day or yesterday's footage, called dailies, and review their work.

While the director concentrates his attention on filming the main scenes—normally the ones in which the stars appear—the task of shooting other footage may be assigned to other units. A second unit is often used for filming in other locations, for shooting fights or other action in which the main actors are not engaged, or for filming street scenes, animals, landscapes, and other such material. Many well-known directors such as Don Siegel, Robert Aldrich, and Jonathan Demme served as second-unit directors early in their careers. The special-effects department may also shoot some footage separately from the main unit, such as the model animation so central to 'King Kong'. During the studio era, some companies also had centralized resources for providing certain services. If, for instance, a film required a close-up of a newspaper headline, the task of filming this would fall to the insert department rather than a crew member dedicated to the particular film. Sometimes standard scenes, such as a cavalry charge, were not filmed at all. Instead, the filmmakers incorporated stock footage drawn from the production company library. This was a far cheaper option than reshooting scenes for each individual picture and was unlikely to be noticed by most viewers.

Although problems encountered during principal photography are common to many films - difficult locations, poor logistics, and recalcitrant actors - the methods that filmmakers use to address them can be very different, as are their outcomes. My Son John (1952), Solomon and Sheba (1959), Dark Blood (1993), and The Crow (1994) all had to deal with the deaths of their lead actors during their shoots. 'My Son John' was completed by incorporating outtakes of Robert Walker from his previous film, Strangers on a Train (1951). 'Solomon and Sheba' recast the role of Solomon, replacing Tyrone Power with Yul Brynner, and reshot all of Power's scenes, while 'The Crow' succeeded in resurrecting its star, Brandon Lee, through the use of computer animation. 'Dark Blood' , however, was abandoned after the death of River Phoenix in 1993, as the insurance company considered this to be the cheapest option.

After principal photography is concluded, the production process moves to postproduction. Postproduction transforms the thousands of feet of raw footage into a finished film. One of the most important elements of postproduction is the editing process in which shots are selected and assembled in an appropriate order.

Editing, like script development, goes through several stages. Traditionally, the editing process has involved working with a physical copy of the film, cutting and splicing pieces of footage manually. It is now more common to load the images onto a computer using a system such as Final Cut Pro or Avid, which allows easy experimentation with different ways of arranging the shots. Whichever method is used, the basic processes remain the same. First, the dailies are assembled in the order specified in the shooting script. Excerpts are then taken from individual shots and arranged in such a way as to tell the story as economically as possible, while at the same time preserving a sense of coherent time and space. This is traditionally referred to as the "rough cut." Although normally it does not have a soundtrack, it is generally a reliable guide to the finished film.

While the editing is taking place, work is carried out on the soundtrack, with different crew members working on the music, sound effects, and dialogue. Music and sound effects must be recorded and the different tracks combined into a final mix. Opening and/or end credits must also be added, and other optical and visual effects work may be required.

When the editing of the image track has been completed, a copy of the original negative is cut to match the edited print. A new positive print, known as an "answer print," is struck from the edited negative. This print is then graded, which ensures that color and light levels are consistent throughout the film. The process may be repeated several times before unwanted variations are eliminated. At the end of this process, a print called an "interpos" is created, from which another negative, called an "interneg," is struck.

Work on the final version of the soundtrack is also completed at this stage. The final sound mix is made to synchronize perfectly with the finished image track, and the sound is recorded onto film in order to create an optical soundtrack. A negative is created from this and combined with the interneg. Any titles and optical effects are also added at this stage. The resulting combined optical print will be the source of the "interdupe" negative, from which the final release prints will be struck.

Throughout postproduction, executives of the producing or distributing company carefully monitor the progress of the film. If dissatisfied with the results, they may insist on changes, sometimes even replacing the original editor and/or director. This may happen at any stage from the rough cut onwards. The insistence of studio executives on their right to determine the final cut has frequently resulted in bitter conflicts with directors who often regard themselves as the "authors" of the finished film. A confrontation that entered the Hollywood annals took place during the studio era between MGM and director Erich von Stroheim. Producers were alarmed by von Stroheim's 42 reel (approximately nine or ten hour) rough cut of Greed (1924). Aware that a film of this length could never be screened commercially, von Stroheim cut almost half the footage himself, and then handed the reduced version to a trusted associate for further editing. The results failed to impress MGM executives, who demanded further cuts. When von Stroheim failed to comply, they appointed their own editor, and cut the film down to the more marketable length of ten reels.

If the studio is uncertain about the audience appeal of a film, it will often undertake test screenings in order to gauge reaction and obtain guidance for improvements. Test screenings may be repeated several times until audience scorecards indicate the film has attained the desired response. Reediting, or even reshooting, may be required if audience reactions fall short of expectations.

Related Articles

Resources