Censorship in the German and Vichy zones forced filmmakers to avoid subject matter relating to the war and other social problems. Much of the Vichy cinema was sheer escapism: American-style comedies like L'honorable Catherine (1943); thrillers: Dernier atout ('Final Trump'), L'assassin habite ... au 21 ('The Murderer Lives at no. 21 '), both 1942; musicals with Tino Rossi, Charles Trenet, or Edith Piaf; costume dramas, such as Pontcarral, colonel d'empire (1942), La duchesse de Langeais (1941), and Les enfants du paradis (1945). One third of all wartime production consisted of literary adaptations, and the period saw the rare appearance of a 'fantastic' trend in French cinema, with films like La nuit fantastique ('The Fantastic Night', 1941), L'éternel retour (on a script by Jean Cocteau), and Les visiteurs du soir". [4]

"The most notable films of this period fit into the prestige category, close to what would later be called the "Tradition of Quality". Belying their straitened circumstances, these films were expert productions, with impressive sets and major stars. Cut off from contemporary reality, they conveyed a mood of romantic resignation. Some films, however - vague allegories of French indomitability - also could be interpreted as suggesting resistance to oppression". [5]

"Marcel Carnè’s Les enfants du paradis ('Children of Paradise', 1945), from a script by Jacques Prévert, was unquestionably one of the major films of the Resistance cinema, using the story of a group of theatrical performers to highlight the resilience of French national culture in the face of the occupying forces. Henri-Georges Clouzot created Le corbeau ('The Raven', 1943), a memorably vicious film documenting the effects of a series of "poison pen" letters on the inhabitants of a provincial French village. Like all of Clouzot’s work, The Raven has a bleak view of humanity, and the town and its citizens in the film are viewed as a gallery of unscrupulous, gossiping, even drug-addicted miscreants. The film was viciously attacked in the Resistance press for its unflattering view of French society, and after the war Clouzot and the film’s screenwriter, Louis Chavance, were banned from making films for a time, as retribution for their deeply misanthropic work. But the ban was soon lifted, and as later Clouzot films make clear, the director’s pessimism was not directed at French society so much as against the human predicament in general; Clouzot was clearly a fatalist who saw life as a continuous battle.

The most important filmmaker to begin a career during the Occupation period was Robert Bresson, whose first feature, Les anges du péché ('Angels of Sin'), appeared in 1943. An audacious film noir set in a convent, it deals with nuns who try to reform female criminals. Bresson's characteristic narrative of spiritual redemption emerged in mature form, with a rebellious nun and a murderess unpredictably helping each other find peace. The austere visual style also looked forward to Bresson's later films. Bresson's next film, Les dames du Bois de Boulogne ('Ladies of the Park', 1945), was created in collaboration with Jean Cocteau, who wrote the dialogue for the film, with the story based on Diderot’s classic "Jacques le fataliste et son maître." Throughout the film, Bresson’s impeccable camera movement and editorial style, coupled with Cocteau’s sparkling and sardonic dialogue, bring this story of moral consequences into sharp detail, and the plight of the heroine is seen as emblematic of France’s position under the Nazis; the illusion of freedom is present but at a terrible cost. Bresson’s later films would be far more minimalist than Les dames du Bois de Boulogne, but in this early masterpiece he created one of the treasures of world cinema". [9]

"French cinema kept a high profile at the Liberation. A Committee for the Liberation of French Cinema was set up, and a journal, L'ecran français, founded. Jewish personnel came back, while, as part of the general epuration, Sacha Guitry, Arletty, and Maurice Chevalier were penalized for fraternizing with Germans (and Clouzot banned from working for two years, on account of Le corbeau), though none had been involved to the extent of actual Fascists like actor Robert Le Vigan (who left France to escape condemnation) or writer Robert Brasillach, shot in 1945. The culmination of the Carné-Prevert Poetic Realist universe, Les enfants du paradis, came out on 9 March 1945. It was a huge popular and critical success, its two central characters, Baptiste (Jean-Louis Barrault) and Garance (Arletty), seen as the embodiment of the indestructible 'spirit of France'". [4]

"The Liberation proved barely less disruptive to the cinema than the Occupation. Collaborators, as we have seen, found their careers blighted or destroyed, while the disappearance of the protected domestic market seemed briefly to threaten the very foundations of the French industry. The Blum-Byrnes agreement of May 1946 allowed American films unrestricted access to the French market, but also introduced a quota of French films to be screened - initially 30 per cent, rising to 38 per cent in 1948. The agreement, widely denounced at the time as an act of treachery, appears in retrospect not only highly realistic, but premonitory of subsequent French cultural and cinematic relations with the USA, seeking accommodation of the 'cultural exception' within an American hegemony the French industry could not hope to vanquish. Along with the nationalisation of large exhibition circuits at the end of the war and the continuation of 'outrageously protectionist' government advances and funding, the agreement protected the industry far more effectively than might have been thought at the time. The Centre national de la cinematographie (CNC) was set up in 1946 to oversee film finance - a striking example of the readiness the French state has always shown to intervene in cultural matters - and in 1948 established a fund to assist French film production and distribution, which has been largely responsible for the industry's high international profile ever since". [6]

Italian Wartime Cinema

"Italy’s ties to Germany strengthened in the late 1930s as both countries assisted future Spanish dictator Francisco Franco’s nationalist forces in the Spanish Civil War (1936–39). Mussolini saw the Rome–Berlin Axis as a chance for Italy to achieve Great Power status, a desire only partially satisfied by Mussolini’s conquest of Ethiopia in 1936 and his exuberant rhetoric claiming that the Empire had finally returned to the "seven hills of Rome" after 20 centuries of history. As WWII broke out, Mussolini initially kept Italy out of the conflict. But Hitler’s early string of successes in Poland, Denmark, Norway, Belgium, and France convinced Mussolini to enter this war on what he mistakenly judged to be the winning side in part to order to avoid the limited territorial concessions of the 'pace mutilata' (mutilated peace as defined by D’Annunzio) peace treaty following WWI". [1]

"Between 1940 and 1942, Italy's battlefield successes boosted the film business. The 1938 legislation had streamlined the industry, creating over a dozen production-distribution combines. The adroit Luigi Freddi, who was by 1941 president of ENIC and supervisor of Cinecittà, revived Cines as a semigovernmental company. Though never as all-embracing as Ufa in Germany, Freddi's Cines produced more films than any other firm during 1942 and 1943. Overall, film attendance increased and output rose to unprecedented levels: 89 features in 1941 and 119 in 1942. This surge in production allowed young directors to start careers, and many of these men would achieve fame in the postwar era.

Even in wartime conditions, however, the regime did not commandeer the industry. The General Direction, under Freddi's successor Eitel Monaco, actually liberalized censorship. More generally, during the late 1930s, anti-Fascist attitudes grew strong among younger intellectuals, who were dismayed by the regime's military adventures and doctrinaire educational system. This atmosphere fostered a broadening of artistic options. One trend looked back to nineteenth-century theatrical traditions. This trend was called calligraphism for its decorative impulses and its retreat from social reality. Typical examples are Renato Castellani's Un colpo di pistola (A Pistol Shot, 1942) and Via della cinque lune (Five Moon Street, 1942), by Luigi Chiarini, the first head of Centro Sperimentale.

A younger generation, however, was debating the merits of realistic art. Influenced by Ernest Hemingway, William Faulkner, and other American authors, writers argued for a return to an Italian tradition of regional naturalism (epitomized in the verismo of Giovanni Verga, a turn-of-the-century novelist). Similarly, in the pages of Bianco e nero, Cinema, and other journals, critics called directors to film the problems of ordinary people in actual surroundings. Aspiring filmmakers were impressed by the Soviet Montage films shown at Centro, by French Poetic Realism, and by Hollywood populist directors like Frank Capra and King Vidor. In 1939, Michelangelo Antonioni envisioned a film about the Po River that would tell a story while recording life along the river. A 1941 essay by Giuseppe De Santis praised American Westerns, Soviet landscape shots, Jean Renoir's 1930s films, and some works of Blasetti as forerunners of an aesthetic that would blend fiction and documentary into a true and genuine Italian cinema". [5]

"Perhaps the most interesting aspect of the Italian wartime cinema, and its greatest legacy, comes from the many young directors who began their cinematic apprenticeship at Mussolini’s state-run film school, including Renato Castellani, Vittorio De Sica, Roberto Rossellini, Pietro Germi, Giuseppe De Santis, and Michelangelo Antonioni, all of whom would go on to great success in the postwar era. These talented cineastes directed films at Cinecittà before or during the war, some in direct support of Mussolini’s regime, others merely designed as dramatic or comedic entertainment.

In the war years, reality inevitably loomed large, and the screenwriters, directors, technicians, and actors who were to be the protagonists of the new realist cinema after 1945 were already working. Three films made during the war revealed the hidden face of an Italy in deep crisis: Quattro passi tra le nuvole, by Blasetti (Four Steps in the Clouds, 1942) and I bambini ci guardano (The Children Are Watching Us, 1942), by De Sica. "These films, very different in style yet marked by a common concern with life as it is actually lived, would have been clear indications that something new was afoot in the Italian cinema even if, in 1943, Ossessione had not already shown with brilliant clarity the way to neorealism.

The world outside, France in particular, knew practically nothing of this lengthy and intricate chain of developments. Italy was cut off from its foreign markets, split by its political conflicts, ravaged by poverty and war, despised for its sudden shifts of policy (the reasons for which remained misunderstood), ridiculed and humiliated; in the eyes of the world, whether friend or foe, it simply did not count. It was as if a decade of blunders had cancelled out the history of twenty centuries, and the arrant supremacy of a single political party had made everyone forget that Italy had a soul. How could anyone have foreseen that within the space of a few years it would come to dominate - artistically, this time - the entire cinema world?" [7]

Britain Can Take It

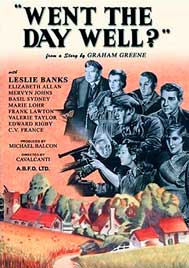

"For the United Kingdom, the war began on September 3, 1939. Anticipating immediate German bombing, the government closed down all film showings and production. Soon it became clear that such measures were unnecessary, and theaters reopened. Military officials did, however, requisition many of the country's film studios for such wartime uses as supply warehouses. Some of the industry's personnel also went into military service.

The Ministry of Information encouraged wartime filmmaking. It required that all film scripts be checked to make sure that they in some way supported the war effort, and producers patriotically cooperated in creating a positive image of Britain. The Ministry of Information even put money into some commercial films. Wartime austerity had made it undesirable to spend money on imported films. Moreover, the new quota was still in effect, and British films were in demand. Due to the lack of studio space and personnel, however, far fewer films were made during the war. From between 150 and 200 annually during the mid-1930s, production sank to just under 70 films a year." [5]

"However, Britons were going to the pictures more than ever; in canteens, Army and Navy Camp Film Societies, factory halls. and mobile vans as well as in cinemas. enduring air raid sirens and evacuations during shows. Cinema has never been as popular in Britain as it was by the end of the Second World War; audiences seemed to thrive on the visual luxury and seeming daring of luminous screen display which contrasted so powerfully with the black-out conditions outside.

The main beneficiary of the wartime film industry was J. Arthur Rank, who by 1943 had amassed assets equivalent to those of an American major: he bought distribution rights to Gaumont-British/Gainsborough in 1937; took over Korda's Denham studio in 1938; acquired Elstree-Amalgamated Studios in 1939; and bought the Odeon chain and Gaumont-British in 1941 when prices were low over the uncertainty of war's effect on screenings. Fifty-six per cent of studio space in Britain was now owned by Rank, and a booking with one of the major exhibition circuits, of which the most important were Rank-owned Gaumont/Odeon and ABC, was essential for the successful exploitation of any feature in the United Kingdom. Rank opted to divert some of his profits to independent filmmakers linked to his organization through an umbrella group, Independent Producers Ltd. Here he supported four important director/producer units: the Archers (Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger); Individual Pictures (Frank Launder and Sidney Gilliat); Cineguild (David Lean, Anthony Havelock-Allan, and Ronald Neame); and Wessex (Ian Dalrymple). By this arrangement Rank contributed to the diversity of film output during and after the war, funding and distributing Powell and Pressburger's The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp (1943) and A Matter of Life and Death (1946), David Lean and Noel Coward's Brief Encounter (1945), and Launder and Gilliat's I See a Dark Stranger(1946).

Others who benefited from the crisis were newsreel and documentary teams, needed to provide official instructional and informational pictures. After two years of war they were busier than ever, showing their wares in touring vans, service camps, and public libraries as well as cinemas. War blurred the distinction between documentary and feature film-making. There was a freer exchange of personnel between the two limbs of the industry because of general staff shortages, and new demands on the medium to represent the realities of fighting Britain. Many feature films incorporated documentary footage offleets, flypasts, parades, and explosions, pulling narratives away from stagy interiors and theatricality.

War produced an acute demand for coherent representations of the nation that showed its divisions - of region, of class, of sex, of age - as underpinning the ultimate identity, character, and above all unity of the country. One response to this need was to adopt documentary strategies for rooting a fiction in the country's present crisis, and pursuing a narrative in which a diverse group of citizens from different regions or different classes are shown pulling together for the common good. Documentary strategies (and existing documentary footage) were adapted for films of the period, including in 1943 Leslie Howard's The Gentle Sex about seven women training and fighting in the Auxiliary Territorial Service; Anthony Asquith's We Dive at Dawn describing the pursuit and sinking of an enemy ship by a British submarine; and Charles Frend's San Demetrio London, based on actual events surrounding a merchant ship bringing oil cargo across the Atlantic to the Clyde." [4]

Germany: The Realm of Illusion

"The outbreak of war provided Goebbels with a new impetus, and he increased his efforts to improve the artistic level of German films, believing that war would act as a catalyst by providing the emotional and artistic stimulus needed for such a ‘revolution’. In practical terms, this meant commissioning a number of extremely expensive political films and increasing the vigilance of the Reich Minister for Popular Enlightenment and Propaganda (Reichsministerium für Volksaufklärung und Propaganda)." [3]

"Members of the Filmwelt, as long as they toed the line, were deferred from military front service on Goebbels' and Hitler's dictum that film workers were soldiers of the Reich on special duty. A request to be transferred to the battle lines was tantamount to treason and the petitioner could be shot for disobeying orders. The number of such applications was small and the dubious privilege of being shot on the Eastern front was granted only to those in official disfavor.

Still, many lesser technical workers were conscripted, causing a cutback in the number of films produced. In 1940, 89 feature films were made, twenty of which with a heavy propaganqa line; in 1941, 71 pictures were completed, twenty-nine banned after the war. With the decrease in the number of productions, more money and time could be spent on making more ambitious projects with greater care than had been possible previously." [2]

"Initially, war presented the Nazis with few problems as it was inexorably linked to their ideology, and therefore easily disseminated by propaganda. However, because of the precarious fortunes of war and the fact that their propaganda was so closely tied to military success, Goebbels had to vary film productions from the overtly militaristic to the purely escapist musical. As the war dragged on, he relied less on political films and more on the escapist element in entertainment genres. Films with a political message were still made, and even in the last two years of the war the most expensive productions were the political or historical epics." [3]

"The vast majority of films made under Goebbels, many revisionist historians now insist, bear few signs of ideological resolve or official intervention. Hitler Youth Quex (1933), Jew Suss (1940), Bismarck (1940), Ohm Kruger (1941), Kolberg (1945), and other state-sponsored productions may well warrant the appellation Nazi propaganda. None the less, such 'state films' constitute a very small portion of the era's films, posing exceptions and not the rule. So-called 'unpolitical' features in fact provided the overwhelming majority; besides a plethora of melodramas, crime stories, and bio-pics, almost 50 per cent of the epoch's films were comedies and musicals, light fare directed by ever-active industry pros like E. W. Emo, Carl Boese, Georg Jacoby, Hans H. Zerlett, and Carl Lamac, peopled with widely revered stars like Hans Albers, Willi Birgel, Marika Rokk, and Zarah Leander, as well as character actors such as Heinz Ruhmann, Paul Kemp, Fita Benkhoff, Theo Lingen, Grete Weiser, Paul Horbiger, and Hans Moser. Many of these films receive recognition as noteworthy achievements, as unblemished classics of German cinema, in some cases even as bearers of subversive energies. Such works seem to demonstrate that the Nazi regime created space for innocent diversions; they reflect a public sphere not completely lorded over by state institutions and reveal an everyday with a much less sinister countenance.

The Nazi public sphere operated along the lines of what Goebbels called an 'orchestral principle'. Not every instrument plays the same thing when we hear a concert; still the result is a symphony. Hardly monolithic or monotone, Nazi culture energized a division of labour between light touches and heavy hands. Films worked together with other forms of diversion (radio programmes, mass rallies, tourist offerings) to organize work and leisure time in an effort to militate against alternative experience and independent thought. State productions and escapist entertainments functioned in tandem so that similarly 'extreme perspectives of extreme uniformity' could be, for instance, found in the party document Triumph des Willens (Triumph of the Will, 1933) and the Tobis musical of 1939, Wir tanzen um die Welt (We're Dancing around the World). Generic pleasure and ideological indoctrination became of a piece. Nazi escapist fare offered no escape from the Nazi status quo.

National Socialism recognized that war involved both material territories and immaterial fields of perception. Film ultimately became a weapon, an explosive arsenal of surprises and effects which made minds reel and emotions surrender under a constant barrage of stimulation." [4]

USSR: The Great Patriotic War

"The wartime Soviet cinema presents an irony. In every country cinema became more controlled by the State, and more heavily propagandistic. In the Soviet Union too, cinema was mobilized for the war effort, and the films produced were obviously propaganda films. Nevertheless, given the immediate past and future of Soviet cinema, the period of the war appears now as an oasis of freedom. The regime allowed a measure of artistic experiment. During the war film-makers engaged with subjects about which they cared deeply and expressed genuinely felt emotions.

In June 1941 Hitler invaded the Soviet Union and German troops advanced rapidly towards Moscow. The leaders of the Soviet film industry dealt with the difficult situation to the best of their abilities and mobilized the industry with astonishing speed. They devoted most of their scarce resources to making documentaries and prevailed on leading directors to take on the task of editing newsreels. Studios changed the scenarios of those features that were already in production by adding war themes. Mashenka, directed by Yuli Raizman, for example, which was almost ready before the invasion, had to be remade. Originally planned as a light comedy showing the happy lives of Soviet youth, its plot was changed so that in the new version, released in 1942, the hero gets his girl by exhibiting heroism in volunteering for the front. Some recently made films in circulation with anti-British or anti-Polish themes were withdrawn, and Mikhail Romm's Mechta (Dream, 1943), which showed the cruelty of the Polish ruling class, was held up for two years. Since the public needed feature films, pre-war movies with patriotic themes such as Piotr pervy (Peter the Great, 1937) and Dovzhenko's Shchors (1939) were revived. Particularly important was Eisenstein's Alexander Nevsky (1938), since it was a bitterly anti-German film which had been taken out of circulation for the duration of the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact.

People craved movies: they wanted to be taken away from their everyday miseries; they wanted hope; they wanted their faith in ultimate victory to be confirmed. Film-going was one of the few remaining forms of entertainment. But in wartime conditions both making and exhibiting films had become extremely difficult Theatres were destroyed, and the number of available projectors in the first years of the war was 'halved. Making films in distant central Asia was fraught with problems. One of the most successful films of the period was Mark Donskoi's Raduga (Rainbow, 1944). Set in wintertime Ukraine, it was shot in Ashkhabad in the summer of 1943 in temperatures of over 40°C; the 'snow' was made of cotton, salt, and mothballs, and the actors had to play their scenes in heavy overcoats, with a doctor on hand in case they collapsed.

Between 1942 and 1945 Soviet studios turned out seventy films (not counting children's films and filmed concerts), of which twenty-one were historical dramas. Films dealing with the experience of soldiers at the front were surprisingly few and, with the exception of Georgi Vasiliev's Front (1943), mostly undistinguished. As long as the fighting continued, there was little desire to romanticize it. Instead of depicting the war as a series of heroic exploits, film-makers preferred to show the barbaric behaviour of the Germans and the quiet heroism and loyalty of ordinary simple people in extraordinary circumstances. The most memorable films of the period, therefore, dealt with the home front and with partisan warfare in German-occupied territories.

Especially in the early films, the Nazis were not only bestially brutal. but also silly and cowardly. The portrayal of decent Germans was vetoed. In 1942 Pudovkin made a film called Ubiytsy rykhodiat na dorugu (Murderers Go Out on the Road), based on stories by Brecht, which attempted to show German victims of Hitler's regime and fear among ordinary citizens, but it was not allowed to be distributed.

The turn from Marxist internationalism to old fashioned patriotism had begun before the outbreak of war, with a spate of films about national heroes in the late 1930s. But during hostilities the process accelerated and films were regularly made to show how a single, great individual (Stalin) could influence history. Almost all historical films made anywhere or at any time are presentist, and aim to appeal to modern audiences by dealing with modern issues. It would be naive to expect Soviet cinema in the midst of a bitter war to have depicted past events dispassionately and for their own sake. Ever so it is extraordinary how brazenly some Soviet films distorted the past. An entire series of films, for example, dealt with the German invasion of the Ukraine in 1918. In these films the Germans are always vicious, the Red Army always manages to defeat them, and Stalin always provides wise leadership." [4]

"From 1943 to 1944, Soviet troops pushed westward, regaining territory and occupying eastern Europe. In early 1945, the Red Army advanced on Berlin, and the German government surrendered on May 8. The war had brought enormous losses to the USSR. The film industry was faced with reestablishing production in the regular studios and rebuilding the Lenfilm facilities, virtually ruined during the Siege of Leningrad. Nevertheless, as one of the victorious powers, the Soviet government retained control of its nationalized film industry." [5]

Japan: The Pacific War

"Japan's all-out attack on China in 1937 marked the beginning of the war in the Pacific. The government banned existing political parties, tightened its alliances with Nazi Germany and fascist Italy, and mobilized the home front around a war-based economy. The film industry was slowly brought into line with the new policies. In this jingoistic atmosphere, western culture became suspect. Studios were ordered not to portray jazz, American dancing, or scenes that might undermine respect for authority, duty to the emperor, and love of family. In April 1939, Japan's Diet passed a law modeled on Goebbel's edicts to the Nazi industry. The Motion Picture Law called for nationalistic films portraying patriotic conduct. The Home Ministry established the Censorship Office, which would review scripts before production and order revisions where necessary.

Although American films were still playing in Japan and some Japanese directors dodged the terms of the new law, political constraints were much stronger than ever before. For instance, the Censorship Office rejected Yasujiro Ozu's script for The Flavor of Green Tea over Rice because the married couple's parting meal was not the "red rice" traditionally reserved for seeing off a warbound husband.

As the Chinese war intensified, the government forced the film companies to consolidate. In 1941, authorities agreed to a three-part reorganization. One group was dominated by Shochiku, another by Toho, and a third, unexpectedly, by the small firm of Shinko. Shinko's key executive was Masaichi Nagata (who had produced Mizoguchi's Naniwa Elegy and Sisters of Gion for his independent firm Dai-Ichi Eiga). Nagata used the consolidation scheme to gain control over Nikkatsu, whose production facilities were absorbed into his group. Nagata' group was renamed Daiei (for Dai-Nihon Eiga, or "Greater Japan Motion Picture Company"). Nikkatsu was allowed to keep its theater holdings separate, so Daiei initially had difficulties in exhibiting its product. After the war, Daiei would become Japan's major force on the international scene.

All companies participated in the war effort. The government supported the production of newsreels, documentary shorts, and films celebrating the uniqueness of Japanese art. Alongside tributes to the purity of Japanese culture were patriotic films supporting the war effort. In attacking American forces at Pearl Harbor in December 1941, Japan declared war on the United States and Britain. Japanese forces seized western colonies throughout the Pacific and soon dominated East and Southeast Asia. By mid-1942, Japan seemed a new imperial power, holding major islands as well as Siam, Burma, Singapore, Vietnam, Hong Kong, Taiwan, and major portions of China. Japan promised to lead the "Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere," but usually the Japanese occupation was at least as harsh as its colonial predecessors.

Full-scale war reduced resources on the home front. The government cut screenings to two and a half hours, rationed film stock, and limited studios to releasing two features per month. Production dwindled to about a hundred features in 1942, seventy in both 1943 and 1944, and fewer than two dozen in 1945. With most men drafted and most women working in factories or community groups, film attendance fell drastically. Patriotic efforts became more shrill. Films celebrated kamikaze raids and the struggle against partisans in China. Toho produced the extravaganza The War at Sea from Hawaii to Malaya (1942), directed by Kajiro Yamamoto and released on the first anniversary of the Pearl Harbor attack. The film's historical sweep and excellent miniatures and special effects made it an outstanding propaganda piece.

Gradually, three years of Allied "island hopping" pushed Japan's forces back. In August 1945, after months of fire bombing Tokyo and other cities, U.S. planes dropped atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Japan surrendered soon afterward. Like most of the nation's institutions, the film studios were hard-hit, but even the devastation of the war and the reforms of American occupation could not loosen the major companies' stranglehold on the industry. The Japanese studio system would retain control for three more decades." [5]

Resources

- [1] Carlo Celli & Marga Cottino-Jones, A New Guide to Italian Cinema (Palgrave Macmilan, 2007) pp 39

- [2] David Stewart Hull, Film in the Third Reich: A Study of the German Cinema, 1933-1945 (University of California, 1969) pp 178

- [3] David Welch, Propaganda and the German Cinema, 1933-1945 (Cinema and Societ) (I. B. Tauris, 2001) pp 159

- [4] Geoffrey Nowell-Smith, The Oxford History of World Cinema (Oxford University Press, 1996) pp 348, 365-69, 377-79, 394-96

- [5] Kristin Thompson & David Bordwell, Film History: An Introduction (McGraw-Hill, 2003) pp 244, 248, 252-54, 270, 272, 279

- [6] Phil Powrie & Keith Reader, French Cinema: A Student's Guide (Bloomsbury Academic, 2002) pp 13

- [7] Pierre Leprohon, The Italian Cinema (International Thomson Publishing, 1972) pp 82-83

- [8] Robert Sklar, A World History of Film (Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 2001) pp 236

- [9] Wheeler Winston Dixon & Gwendolyn Foster, A Short History of Film (Rutgers University Press, 2008) pp 137, 159-60